The environmental impacts of the Interstate Highway System continue to harm communities of color through health hazards, pollution, and displacement.

The sprawling roadway network of the Interstate Highway System (IHS) is a ubiquitous feature of life in America. Long drives along vast stretches of freeway have come to symbolize mobility and freedom in cultural memory, obscuring the insidious nature of the creation of the highway system and its legacies of environmental racism and inequality.

These legacies are not abstract; they have tangible effects in terms of pollution, population displacement, and environmental degradation. To illustrate this point, we’ll start with a story.

The community of Shiloh in Coffee County, Alabama

Highways can endanger lives by exacerbating negative health and safety outcomes. This is exemplified in the ongoing injustices against the predominantly Black community of Shiloh in Coffee County, located in the rural south of Alabama, where the expansion of Highway 84 from 2 to 4 lanes has compounded flooding impacts for the residents. Completed in 2018, the highway expansion project elevated the roadway significantly higher than the existing terrain and neighborhood.

When it rains, the water from the highway is diverted towards people’s homes (as you can see in this video from ABC News) as pipes in the drainage system are pointed in the direction of the neighborhood. Paved roadways are also particularly impervious to stormwater and create substantial run-off, which picks up additives such as rust, metals, and pesticides. The Shiloh community consistently experiences flooding, and with heavy rain becoming increasingly frequent due to climate change, the situation is only expected to worsen. Flooding has affected the structural integrity of homes and is raising alarming health concerns with residents reporting the appearance of mold. Physical damages and rising maintenance issues have forced the Shiloh community to contend with the difficult reality of investing in expensive repair projects or leaving their homes.

The Shiloh community has been working to bring awareness to the plight and adversity they have been experiencing for the past 6 years, in a political landscape that has largely neglected to address the severity of the environmental disaster created in their backyard. Alabama DOT (ALDOT) continues to maintain that no discrimination took place when they planned the highway widening project and that the flooding is not a consequence of the expansion. Following community complaints, three residents received settlements of $5000 or less in exchange for restrictive covenants on their property that release ALDOT from any responsibility of flood damage, which is the extent of any action taken by the state.

Robert Bullard, popularly known as the “father of environmental justice,” has also been collaborating with the community to demand accountability at the federal level. Their efforts culminated in an ongoing civil rights investigation from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and a visit from the U.S. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg in early April of this year. But so far, no real relief has been found. The residents that signed away their rights feel misled and misheard, with the fear that their homes—and all the wealth and history they hold—are being washed away.

A compounding price

While the community of Shiloh’s case is an extreme example, countless communities across the country are harmed by existing highways and highway expansion projects. The highway system was constructed in a way that cut through vibrant existing neighborhoods, plowing through the heart of communities of color. This build-out of infrastructure cemented racial divides and segregation, encouraging connectivity for certain communities at the expense of others.

Inequities produced by the highway system are reinforced daily, with communities neighboring freeways bearing a disproportionate share of environmental harm. The siting of highways has historically exposed low-income communities and communities of color to higher amounts of air, water, and noise pollutants which in turn produces higher risk for disease and illness. Research indicates that there is a higher exposure to air contaminants for these communities which increases risk for cardiovascular disease and lung problems, among other health concerns. Proximity to paved surfaces, which absorb more heat than natural surfaces, means that communities are subjected to extreme heat as well.

Residents of Little Village, a predominantly Hispanic community in Chicago, have had to contend with poor quality air as a constant feature of their neighborhood that is located in close proximity to Interstate 55. Despite this, a proposal was introduced to add new lanes to the highway, incentivizing increased traffic, leading to a higher concentration of air pollutants in the region and a litany of detrimental health effects. Similarly, a controversial expansion of I-45 in North Houston is set to start soon, which would displace communities and add to existing problems of air pollution.

One of the regulatory tools that the public has at their disposal to challenge administrative actions is the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). Enacted in 1970, NEPA requires agencies to produce detailed statements on the environmental impacts of a project, potential actions to mitigate damage, and alternative projects with lower impact. Periods for public comment are integrated into the process as opportunities for affected communities to raise concerns and ensure that their considerations are involved in the decision-making process. Although NEPA gives the public a platform to voice their concerns about projects, it is not designed to stop these projects from being implemented, even if they may cause significant environmental harm. This means that infrastructure projects, such as highway construction and expansion, can continue to move forward even when the repercussions on environmental justice are clear.

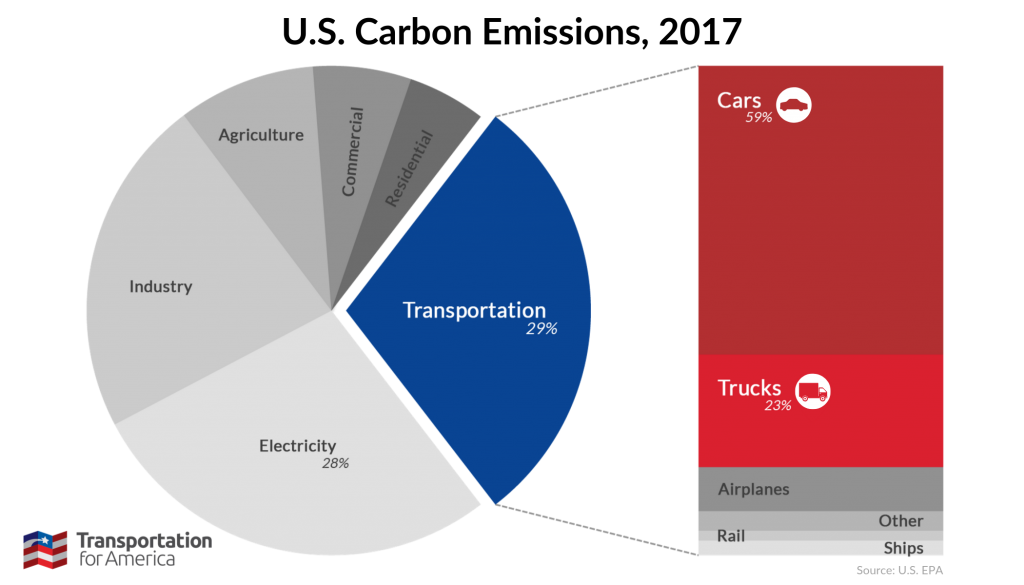

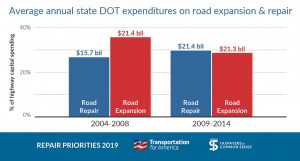

Recent research and analysis conducted by T4A has found that trends of highway expansion are continuing to stay the same. Funding is being moved towards emissions-increasing roadway widenings at a critical moment in the climate crisis when our dollars should be spent towards robust public and alternative transportation options. Our transportation system is steeped in environmental racism and continues to function as a driver of inequality. It has created countless socio-economic benefits for certain communities at the tremendous expense of others. Changing weather patterns have also unearthed the fragility of our transportation networks and the need for resilience to allow them to withstand vulnerability.

As the current administration works towards building a future for transportation infrastructure that is equitable and sustainable, it is presented with an opportunity to radically redress historic inequities and meaningfully change how we invest our federal transportation dollars and prioritize who we invest in. Our report, Divided by Design, explains further. Read it here.

Politicians (and the media) love to bemoan our “crumbling roads and bridges.” That must mean we need more money to fix them, right? Here’s a secret: most of the billions we spend every year on our infrastructure

Politicians (and the media) love to bemoan our “crumbling roads and bridges.” That must mean we need more money to fix them, right? Here’s a secret: most of the billions we spend every year on our infrastructure