Transportation network companies (TNCs) like Uber and Lyft and bike-share providers like Zagster can improve options and expand accessibility. Can they support vulnerable populations and smaller markets? Transportation for America attended the Shared Use Mobility Summit to learn more. (This is part one of a two-part series.)

PC: Marin County Media

In the United States, individuals miss over 3.6 million medical appointments every year due to lack of transportation, according to a 2013 article in the Journal of Community Health. And according to the Kessler Foundation, access for people with disabilities has not improved since 1998; it’s actually getting harder to get around. This has a disproportionate impact on vulnerable populations.

Senior shuttles and paratransit fill some of these gaps in access, which are growing unfortunately, but they are often limited in the populations, destinations and hours that they serve. These services can be expensive for providers, and inconvenient for customers, who often need to order a ride 24-48 hours in advance.

In towns, cities and places of all sizes, questions are emerging about the role of new mobility providers like Uber, Lyft and other TNCs in filling these gaps and becoming part of how we ensure mobility for these groups of people. What would it look like? What are the concerns that cities need to be aware of as they think about using any of them to help meet their needs?

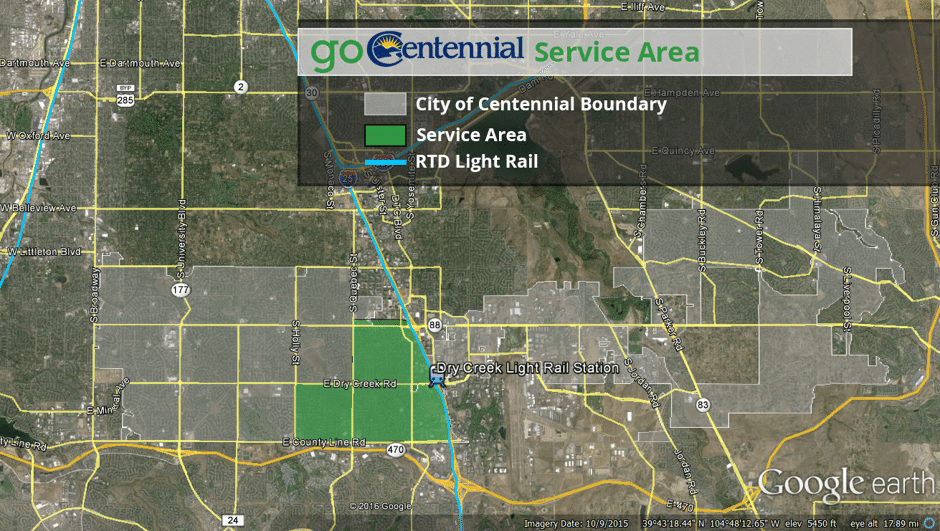

The Centennial pilot

Centennial, CO, a suburb 13 miles south of Denver, has a fairly typical first- and last-mile problem; its Denver Regional Transportation Authority light rail station is far away from its residential, retail, and job centers. Cost and hour-plus wait times have made its dial-a-ride service unappealing. But in August of 2016, the city partnered with ride-hailing service Lyft to launch a six-month pilot program in an effort to change that. (Centennial is also one of the 17 cities in our Smart Cities Collaborative, and we heard a great deal about these efforts during our inaugural meeting back in November.)

The Go Centennial pilot allows residents to catch a free (subsidized by the city) Lyft ride to or from the light rail station. A local paratransit company has also joined the Lyft platform with accessible vehicles to enhance service. And to help serve people who would prefer to call for a ride rather than using a smartphone application, the city has partnered with a developer to create a web application that the city can use to dispatch rides to those customers.

PC: Peter Jones, Villager Publishing

For Centennial, the project has so far been a fiscal success: total project costs for the city have been about half of subsidizing the previous dial-a-ride service.

“Public-private partnerships with aging, disability, and other groups have become a growing mandate as we come to realize how much we have in common,” says Andrew Salzberg, head of Transportation Policy and Research at Uber. Uber is currently partnering with 20 cities to provide wheelchair accessible vehicles & lease them to drivers. Many cities have joined Centennial in subsidizing TNC services to supplement paratransit service.

A pioneering transit agency

Some cities are working to get ahead of the curve by developing their own solutions. Kansas City, Missouri partnered with Bridj to pilot an app-based, on-demand shuttle service in select areas of the city to make it easier for people to get around.

“We have to look beyond traditional transit, even reinvent what transit agencies are,” says Robbie Makinen, president & CEO of the Kansas City Area Transportation Authority (KCATA), showing a remarkable amount of foresight to think outside the conventional work of a transit agency. “As we explore new mobility options the opportunity to partner with the private sector is tremendous.” he says.

PC: Daily Republic

This winter, the KCATA will launch an on-demand paratransit service called RideKC Freedom. “RideKC Freedom is going to start with the paratransit piece and build out, which is the opposite of what typically happens,” he says. While many transportation systems offer paratransit as a supplementary service, the goal of RideKC Freedom is to begin as a paratransit service before eventually expanding as a shuttle service intended for all users.

Makinen believes that for too many years, the most vulnerable riders have been left to navigate a transportation system that limits their ability to access opportunities. “We will leverage our private sector partnerships to reduce per trip paratransit costs, and then expand RideKC Freedom into serving the broader retail market, he says.” This business model is designed to eliminate social stigmatism associated with using paratransit service, and create a new funding stream.

Service for seniors

Based in San Francisco, CA one company fills a special niche. SilverRide provides call-ahead, escorted rides for senior citizens or anyone who needs additional help due to physical or cognitive challenges. Drivers receive extra training from the company on how to handle common medical conditions and provide physical assistance. The service also provides notes about any special help passengers may need.

“Seniors and those with disabilities tend to need more hand-holding than the general public,” says SilverRide CEO Jeff Maltz. That’s why passengers receive personalized customer care and frequent reminders about their scheduled rides. And the escort aspect ensures those who need door-through-door assistance can use the service.

SilverRide comes at a slightly higher price tag, which Maltz says is the necessary to provide a resource tailored to serve populations with different needs.

“Any service that offers the extra assistance to accommodate folks who have special needs has added cost to accommodate the extra need. We have removed as much cost as possible by offering a TNC-plus model that can plug into any system in a variety of ways to make sure the needs of all riders are met.” He notes that a one-size-fits-all approach has traditionally led to poorer service and higher costs, and argues that tailored solutions combined with technology and improved regulations are a better approach.

PC: Ride Connection

Designing for the elderly and people with disabilities is important in all systems, notes Sarah Rienhoff. Rienhoff is the public sector lead at Via, another TNC. Her perspective is informed by her past experience working at the global design and innovation firm IDEO. “We should aim to design for inclusivity, looking at ‘extreme’ users, the elderly in this case, to guide our work,” she says.

Rienhoff explains, “When designers take on a problem, they spend time in the edges of the bell curve, with the extremes. By designing for people that most acutely experience the positives or negatives of a product or service, you can also benefit the middle, people who likely experience those same positives or negatives, but to a lesser degree. Rienhoff argues that this is something that many of our transit agencies already do well. “They think about designing services to be universally accessible,” she says.

Maltz agrees it is wise to take best practices from each tailored solution and incorporate those across the board where improvements can be made. he says. And Jana Lynott, senior policy advisor for AARP’s Public Policy Institute, reconciles, “While public transportation should be designed to serve the needs of everyone, there may be cases where older adults are too frail or suffer from dementia where it would not be safe for them to use fixed route public transit on their own.”

Services like SilverRide and Via, when licensed to a transit provider, can serve an important niche. “We also need to design for caregivers,” she says. “They want to be able to schedule rides remotely and track that progress as well.”

Rural coverage

As TNCs grow into smaller cities and suburban markets, options for rural regions lag behind. Uber, for example, considers regions just under 100,000 in population its smallest market.

PC: Zagster

Lynott notes that more services are coming online in rural areas. The national franchise ITN America is the nation’s largest provider of transportation for seniors, providing demand-response service, and more recently Liberty Mobility Now has launched a ride-sharing service intended to compliment the existing transportation in rural communities and provide gap coverage.

As more services come online, it is clear that the market is adapting. But what challenges does that present? And can the public sector and local stakeholders keep up? In our next post, we’ll take a closer look at some of the issues these new TNCs pose. We’ll also review how the bike-share market is responding to different market considerations.