The Congestion Con: How more money and more lanes = more traffic

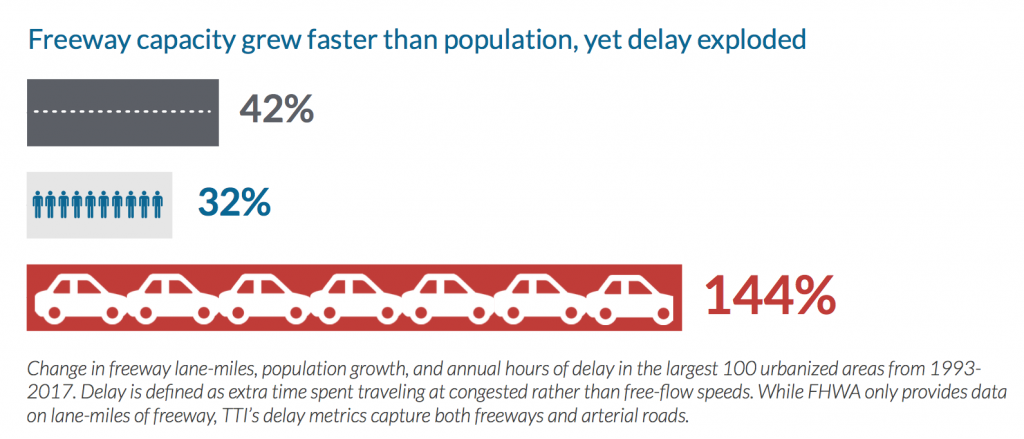

In an expensive effort to curb congestion in urban regions, we have overwhelmingly prioritized one strategy: we have spent decades and hundreds of billions of dollars widening and building new highways. But this strategy has utterly failed to “solve” the problem at hand—delay went up in those urbanized areas by a staggering 144 percent. This report examines why our strategies to reduce congestion are failing, why eliminating congestion might actually be the wrong goal, and how spending billions to expand highways can actually make congestion worse. It includes five simple policy recommendations to make better use of our billions of dollars without pouring yet more into a black hole of congestion “mitigation.”

More about the Congestion Con

We added 30,511 new freeway lane-miles of road in the largest 100 urbanized areas between 1993 and 2017, an increase of 42 percent. That rate of freeway expansion significantly outstripped the 32 percent growth in population in those regions over the same time period. Yet this strategy has utterly failed to “solve” the problem at hand—delay is up in those urbanized areas by a staggering 144 percent.

Those new lane-miles haven’t come cheap and we are spending billions to widen roads and seeing unimpressive, unpredictable results in return. Further, the urbanized areas expanding their freeways more rapidly aren’t necessarily having more success curbing congestion—in fact, in many cases the opposite is true.

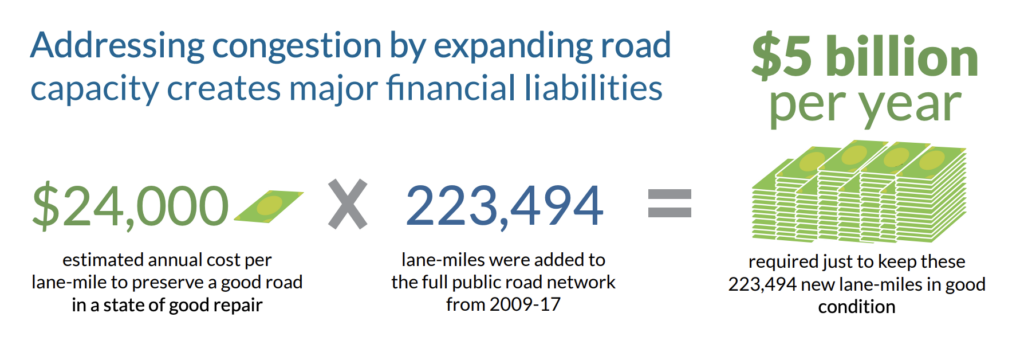

The Federal Highway Administration estimates that a single new lane-mile of freeway in urban areas can cost anywhere from $4.2 million to $15.4 million to construct, depending on the urbanized area size.2 And those initial construction costs are just the tip of the iceberg. Each new lane-mile of road costs approximately $24,000 per year to maintain in a state of good repair, which means that our current approach also creates significant financial liabilities now and for years into the future, whether or not it “solves” the problem.

Understanding induced demand

Even if we hit the most ambitious targets for changing our cars and trucks over to electric vehicles, we will fail to meaningfully reduce emissions from transportation without confronting this simple fact: new roads always produce new driving. This costly feedback loop referred to as “induced demand” is the invisible force short-circuiting the neverending attempts to eliminate congestion by building or expanding roads.

This short illustration explains this concept, and read a longer explainer here.

It would be bad enough if we were simply spending billions to combat congestion and failing to produce results. However, expanding highways to improve traffic flow can actually increase congestion by encouraging people to drive more than they otherwise would. This is a counterintuitive but well-documented phenomenon known as induced demand. 10 Decision-makers sometimes equate congestion to plumbing—to accommodate heavier water flow you need to widen the pipe. But people aren’t like water molecules. They make different choices and change their behavior when new options become available. Economic doctrine holds that in most circumstances, when prices go down, people consume more. In this case, when travel times decrease and driving becomes more convenient, people drive more. We are caught in an extended vicious cycle of widening highways and seeing more traffic follow.