Fight for your Ride

An advocate's guide for expanding and improving transit

Fight For Your Ride: An advocate’s guide for improving & expanding transit, offers local advocates and transit champions practical advice for making real improvements to public transit. Drawing examples from successful campaigns and reform efforts in small, medium, and large cities across the country, the guide illuminates effective ways to speed up transit, expand its reach, and improve service for riders. It offers tactical lessons on building a coalition, developing an effective message, and organizing a campaign for better transit in your community.

This guide aims to do two things:

One, offer tangible steps that local champions can take to make transit service better and show how diverse coalitions of advocates and local leaders have been at the forefront of successful efforts to improve or expand transit service. Use this guide to diagnose the challenges facing your region’s transit system, learn what tools can improve transit service, and read stories that illustrate how other regions have successfully enacted those strategies.

Two, in light of the existential threat to transit currently unfolding at the federal level, provide approaches and examples to organize local advocates in order to support continued federal investment in transit.

Streetcar stop in Portland, OR. (Photo credit: Ian Sane, Flickr.)

Download the guidebook

Thanks for your interest in the guide. Download a full PDF copy of the guide here, or browse the full content below.

Kickoff webinar

At 2 p.m. EST on Thursday February, 8, join us to hear Karen Rindge, Executive Director of WakeUP Wake County, and Christof Spieler, board member for Houston METRO, share stories about their successful efforts to improve and expand transit.

Share this guide

Browse the full guide with the tabs below

Browse the full guide with the tabs below

Introduction

Amazon dropped a bombshell in September 2017 when it announced that it was planning to expand and seeking a city in which to open a second headquarters with room to house as many as 50,000 new employees. In its request for proposals from cities, Amazon stated its clear preference to open their new HQ2 in a city with good transportation access generally and with a robust transit network specifically. The surprise announcement led to a race of public statements from mayors and governors eager to state their case, followed by plenty of clear-eyed assessments and realizations from analysts and even city leaders that while they might have ample land, a business-friendly climate, and even a state ready to offer generous subsidies, the lack of a public transportation network would hurt their chances. As Laura Bliss put it in CityLab, “The emphasis on transit seems to be creating, in particular, something of a come-to-Jesus moment for cities where high-level service has long been an afterthought.”

Amazon’s announcement is just more evidence that the essential recipe for economic development is changing. Talented workers are seeking vibrant, walkable, connected places to call home before finding jobs. And the companies that want to hire them are increasingly looking to move to those in-demand downtown locations to be close to that talent. Cities of all sizes—whether in the running for Amazon or not—are realizing that investing in a range of transportation options is critical to attracting talent and the businesses that follow them.

But investing in transit isn’t just a tool to attract the best and brightest talent. To build broad prosperity and improve access to opportunity for everyone, each region must build a transportation network that helps everyone reach jobs and services, even without a car. Like few other tools, transit can physically stitch together a region to expand access, connect workers and employers, and build strong neighborhoods and communities.

However, in many regions, public transportation service isn’t up to the task, offering infrequent, slow service and poor access to job centers or critical destinations. Poor service turns away potential riders and punishes those who must rely on transit.

Cuts to federal transit funding

Compounding these problems is the ongoing assault by Congress and the presidential administration on the federal transit funding that is the lifeblood of expanding and improving transit service in cities of all sizes. President Trump’s FY2018 budget proposes to entirely eliminate the program for building new transit lines or service, putting the screws to local communities that have raised billions in their own dollars to build vital projects. And in fact, only three new federally supported projects to expand transit service have been approved for new funding since this administration took office in 2017. “Future investments in new transit projects would be funded by the localities that use and benefit from these localized projects,” the administration’s budget document reads.

While the handful of projects that already have what’s known as full funding grant agreements (FFGAs) already in hand would (theoretically) be allowed to proceed, this means that all other future transit projects would be out of luck. The House has already passed a budget for 2018 with zero dollars for new transit expansion projects that weren’t already underway before this year. This means that cities like Seattle, Los Angeles, Atlanta, Indianapolis, and scores of others who recently voted to raise new revenues for transit would be left to fund those projects entirely on their own, which was not the promise made to voters.

Representatives from Seattle and Los Angeles both issued statements earlier in 2017 making it clear that while they—and dozens of other regions—are raising their own money to invest in transit, they are counting on the federal government to continue their historic role as a funding partner in these efforts.

But the threat to the Transit Capital Investments Grant program, as it’s called, is far from the only current threat to transit funding. There’s a good chance that Congress could repeat their failed 2012 effort to entirely eliminate transit funding sourced from the highway trust fund, ending the 80/20 split for highways and transit funding engineered by President Ronald Reagan in the early 1980s. Formula grants are typically used to buy new buses or railcars, but they literally keep smaller systems running, paying for 66 percent of capital expenses and 33 percent of operating expenses for transit systems in areas under 50,000 in population.

Local advocates can’t merely concern themselves with how to build a winning coalition to advocate for additional local or state funding or improvements to transit. Without successfully defending transit to an increasingly skeptical Congress—outlined in the first section below—local advocates will be in an even more difficult position when the bill comes due.

At a time when one of the biggest American companies has made it clear that transit is an essential component for choosing a site for a second headquarters, the federal government is trying to walk out on their historic role as a funding partner for transit projects.

Campaign Tactics

- Urge your representatives to preserve funding for transit.

- Build a winning coalition.

- Craft a winning message.

Urge your representatives to preserve funding for transit

Public transit systems in communities across the country depend on federal funding, which offsets the cost of purchasing and maintaining buses, building new transit systems, and operating smaller and rural transit networks. The federal government invests more than $10 billion annually in public transit as part of a long-standing commitment to a multimodal and connected transportation system linking communities nationwide.

Unfortunately, these critical investments in public transit are now under threat.

The Trump administration’s first budget proposal called for ending the Capital Investment Grant program, which matches local funds to build new, high-capacity transit systems and make upgrades to existing rail transit systems. It also calls for ending the TIGER program, one of the only sources of funding available directly to local communities for multimodal projects like complete streets connections and small-scale capital projects to improve transit. Funding proposals in the House and Senate also call for cuts to transit programs.

Your leadership locally can improve your local transit systems by expanding and improving service. But your local transit success also depends on a continued commitment from federal partners.

Advocate today to ensure your federal representatives know how important public transit is in your community and how important continued federal funding will be to your community’s future.

What you need to do today

- Tell Congress and the president that funding for all transit programs must be preserved—and if anything, should be increased.

- Tell Congress to reject the administration’s proposals to reduce or eliminate funding for transit capital construction.

What you can do tomorrow

- Keep the drumbeat of your own story alive.

- Invite members of your congressional delegation to a “ride-along” on a local transit route or to tour a recent federally funded capital improvement project.

- Host a meeting in district where your member of Congress can meet transit riders.

- Write a letter to the editor or an op-ed for the local newspaper about the importance of your transit system—and share it with your member of Congress once published.

- Speak with and educate local reporters about potential funding cuts and illustrate the impacts of those cuts for your riders and your community.

- Highlight the manufacturers in your district that have jobs supported by transit spending elsewhere. For example, recent transit capital projects in Portland, OR are supporting manufacturing jobs in Oregon, Washington, California, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts.

Build a winning coalition

You will need a united force to succeed. The good news is that better transit can and should draw diverse advocates.

Like few other issues, the movement for better public transit has the potential to unite a broad coalition, creating common cause for strange bedfellows. It takes a united coalition of many diverse voices to affect meaningful improvements.

Building and uniting a coalition takes work. The first step in coalition-building is to listen. It’s likely that there are already extant coalitions that could be joined into your cause. Hold meetings and listen to these groups’ concerns and priorities. Hold meetings with other groups in your neighborhood or across your region who face similar transit challenges or who want to see transit improvements.

Once you understand the networks of supporters and their priorities, develop a common set of principles or a formal request. Having diverse groups sign on to a single set of priorities or a specific ask will solidify the coalition.

Examples

Los Angeles: California law requires a two-thirds supermajority on referenda to approve new local taxes. Winning that level of support for new transit—across a large, diverse county that is nationally known as the center of car culture—required a major coalition led by Move LA. Read more here.

Baton Rouge: It took a broad coalition of equity advocates and civic organizations to fight against cuts to Baton Rouge’s transit service. The coalition won support in a voter referendum and a coalition of civic leaders has held the transit agency accountable. Read the longer Baton Rouge story at the conclusion of this document, one of three case studies included in this guide.

Clayton County, GA: In Clayton County, Georgia, the Partnership for Southern Equity organized a network of front-line community groups to persuade the county commission to put forward a transit funding measure and mobilize voters to approve the new sales tax. A prominent association of ministers was an important ally and the transit campaign used church services to get out the message and build support. Read more here.

Indianapolis: A combined effort by business leaders, grassroots equity and faith groups, and public agencies led to a victory at the ballot box for new transit funding in 2016. Read the full Indianapolis story at the conclusion of this document, one of three longer case studies included in this guide.

Craft a winning message

With a strong coalition in hand, the right message needs to be carefully crafted. Even the strongest coalition can fail without a unified message and everyone singing from the same songsheet.

Make a clear case for why transit is important for your region, how transit can improve, and how better transit will benefit everyone. Show how improved transit will benefit the entire region and how it will help meet your region’s urgent needs and support your community’s aspirations.

Be clear and specific about the challenges that transit riders face and how shortcomings in transit service harm the region overall.

Be clear and specific about how your transit service will improve. If you are asking voters or government agencies to approve additional funding, be sure they know what they will be buying and what benefits they will see from that investment. While more than to 70 percent of local transportation ballot measures typically pass, many of those that fail do so because they are not specific about what that new revenue will buy—what will be improved. Voters need to know specifically what will be built and where, and they need to have confidence that the projects funded will support a larger plan.

Use authentic messengers from across your community who speak to why they or their constituents depend on better transit.

Messages focused on economic development, jobs, and expanded access to opportunity may have the broadest appeal.

More advice on successful campaign communication is available here.

Examples

St. Louis: A grassroots-led campaign won broad support for transit by showing how everyone in the region would benefit from a system that would expand residents access to jobs and opportunity. The campaign won on the simple message, “Transit: Some of us ride it. All of us need it.”

A billboard with simple message supporting transit. (Photo courtesy of Citizens for Modern Transit.)

Boston: Youth advocates used individual stories drawn from community surveys to show how high transit fares were keeping students and youth from reaching jobs, after school activities, and other opportunities. Advocates used high-visibility marches and demonstrations to continually call attention to their cause. Read the full Boston story at the conclusion of this document, one of three longer case studies included in this guide.

Phoenix: Backers of a transit referendum in Phoenix used a clear, direct message and engaged with supporters of all stripes through social media outlets. The referendum was timed to follow the celebratory opening of a new light rail line when transit was in the spotlight. And the campaign benefited from high-level supporters—especially Phoenix Mayor Greg Stanton—who outweighed anti-tax messengers. Read more here.

What can be done to improve transit?

It’s easy to find out what your transit system needs: Ask riders!

If your plans for improving transit or proposing pricey expansions weren’t sourced from existing or potential riders, they are likely to fail. Too often, transit plans come from community leaders—or even transit board members—who never regularly ride on local transit or have a poor mechanism to solicit useful feedback from their most important potential source: riders.

The surest way to assess your transit system’s challenges and begin building support for improvements is to ask riders and potential riders about their experiences and what they need.

Recent polling from TransitCenter shows the top factors driving satisfaction with transit are service frequency and travel time. In contrast, amenities like power outlets and wi-fi on transit vehicles are not an important factor to riders. Read more here.

“My most important piece of advice is talk to the riders. Find out what’s on their minds. Is it unreliable or inadequate service, not enough at night, too little on the weekend? Is it the fare? Do they want discounts? Is the system aging badly, with not enough money for repair? Is it unsafe? Too crowded? And while you are at it, talk to established grassroots groups and labor unions and find out what their members care about.”

— Gene Russionoff, Staff Attorney, Straphanger’s Campaign.

Click the heading area to expand each section

Improving transit and strengthening neighborhoods across your city may depend on adding more transit service or building new transit lines. Big, transformative capital projects, such as light rail and bus rapid transit projects, can anchor new development and significantly improve transit service on high-trafficked corridors. These projects are costly and take many years to develop and build.

Major capital investments in transit have depended on matching funding from the federal government. Through the transit capital construction program, the Federal Transit Administration covers up to half the cost of capital construction.

However, this critical funding program is at risk. The Trump administration has proposed ending the program and is stalling new funding intended to flow to shovel-ready projects. Congress must annually appropriate funding to this program and in their FY2018 funding bills both the House and Senate proposed cutting funding to this program.

Advocates across the country need to let their members of Congress know how important transit is to their communities and how vital this funding will be to local plans to improve transit. See page 9 for actions you can take to protect this federal funding.

Expanding existing service can be a faster way to address the shortcomings of your region’s existing transit system. Added service can extend hours (such as providing service later into the evening or on weekends), increase the frequency of service to reduce wait times or alleviate crowding, or extend the reach or transit to serve new destinations. Providing new service requires additional ongoing operating funding and may also require capital funding (such as the purchase of new buses) to launch.

Downtown bus and rail transit tunnel in Seattle. (Photo credit: Lightpattern Productions.)

When major transportation projects are planned and designed, transit and community advocates have important roles ensuring that transit will meet the needs of riders and neighborhoods that depend on quality transit.

Example

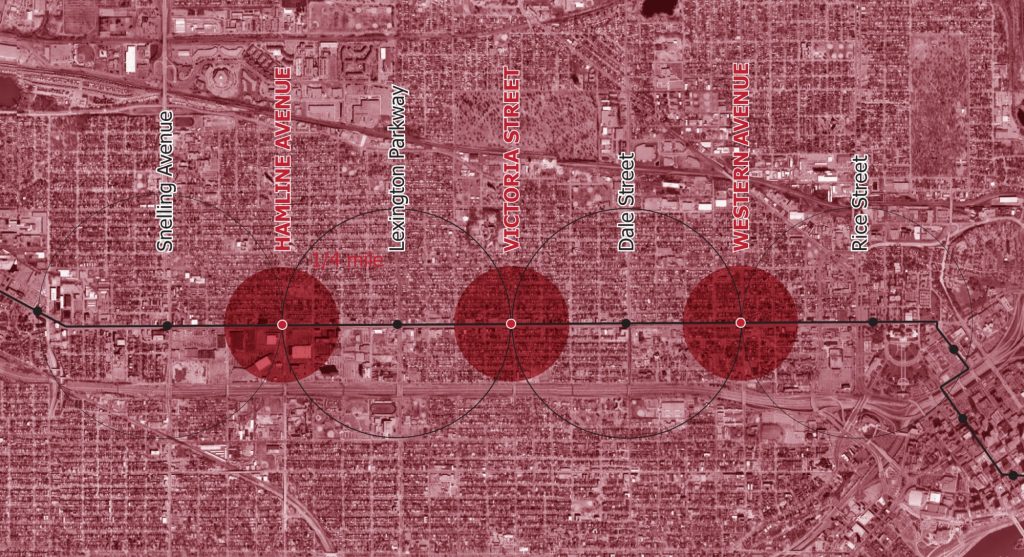

St. Paul, MN: When a new light rail line was planned to traverse several St. Paul neighborhoods without stops that would serve those neighborhoods, twenty grassroots groups organized the Stops for Us coalition and succeeded in changing the plan to add new stops. Read more here.

In those neighborhoods where residents used the existing bus lines in the greatest numbers, planned stations were positioned one mile apart, as opposed to more typical ½-mile spacing in other parts of the corridor. As more and more residents began voicing concerns, a coalition of more than 20 grassroots organizations came together as the Stops for Us Coalition, with a primary focus on securing three additional stations. The proposed and the missing stops on the Green Line are highlighted above. (Photo courtesy of Stop for Us coalition.)

.

Extending the hours of service of transit allows transit to be useful to more people, more hours of the day. Service early in the morning or late at night may be especially important for people commuting to jobs with non-traditional hours, such as service-sector workers traveling home from restaurants or hospital workers heading to early shifts.

Examples

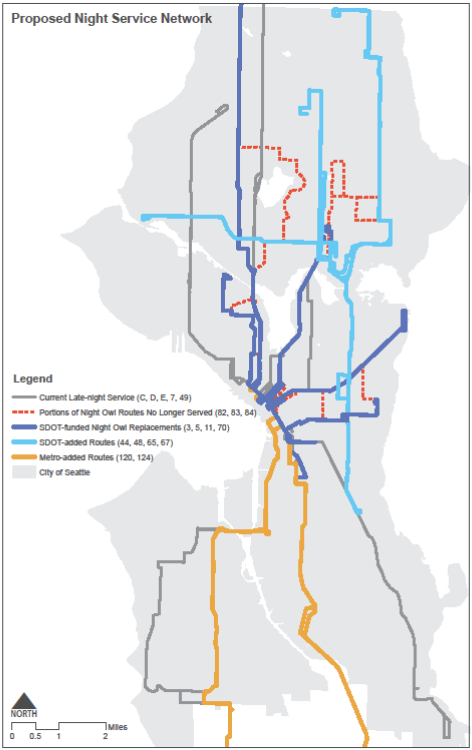

Seattle: After outreach that drew 4,500 responses, the City of Seattle and King County announced a plan to expand overnight transit service. The increased service comes with a price tag of $730,000 annually, of which the city would cover $500,000 though a special transit fund approved by voters. The county transit agency would cover the remainder.

“Giving people affordable, reliable, and convenient transportation choices is key to Seattle’s top two priorities—equity and sustainability,” said Seattle Mayor Ed Murray in a release announcing the plan. “This is particularly important for working families and people of color who are hit disproportionately by the increasing cost of transportation.” Read more here.

Seattle’s “Night Owl” investments that were implemented in September 2017. (Photo credit: SDOT)

Bay Area: The San Francisco Bay region has a growing program to provide late-night bus service after BART trains stop running. BART, the regional rail operator, heard growing pressure from riders to extend hours of rail service, but the agency could not eliminate the night-time windows for track maintenance. BART instead supported late night bus service. In 2016 a pilot program increased service so buses arrive every twenty minutes, instead of half-hourly. The six-month extension of late-night bus service is funded with $73,000 from BART and another $177,000 from the regional transportation planning agency, MTC. Service is operated by a local transit agency, AC Transit.

“It’s one of our missions to make sure that people have mobility options, and that obligation in the Bay Area doesn’t end after midnight,” said Michael Eshleman, AC Transit’s manager of service planning. Read more here.

Shortfalls in dedicated revenue sources or budget cuts imperil transit service and sometimes transit champions must advocate for new funding simply to preserve and continue existing transit service.

As Congress considers cuts to transit funding, these approaches for maintaining funding for vital service and keeping projects on track are critical.

Examples

Baton Rouge: A broad coalition of equity advocates and civic organizations won voter approval for new funding to avoid drastic cuts to Baton Rouge’s transit service. Read the full Baton Rouge story at the conclusion of this document, one of three longer case studies included in this guide.

Minneapolis: Plans for the next pieces of the Twin Cities’ growing transit network have long been in development and construction on the Orange Line bus rapid transit line and the Southwest Light Rail line were both planned to start in 2016. But when suburban Dakota County backed out of support for the Orange Line and the state legislature failed to approve the previously-agreed 10 percent of the light rail line’s cost, both projects were suddenly in jeopardy.

Transit for Livable Communities, a local advocacy group, worked with the Sierra Club, the Amalgamated Transit Union Local, and local elected leaders to mobilize residents to back continued funding for the lines. In August 2016 a bus load of Orange Line supporters, wearing orange shirts and carrying homemade signs packed the meeting of the Counties Transit Improvement Board, the regional government funding the Orange Line project. Supporters cheered when, after a heated discussion, the Board agreed to allocate the funding needed to keep the project on track. Read more here.

Just weeks later, transit supporters focused attention on the Southwest Line, directing appeals to Gov. Mark Dayton and turning out 100 people to a public forum. Another agreement for local funding saved this project and allowed it to move forward. Read more here.

There are low-cost or even cost-neutral ways to reroute transit service that can provide better service for riders. However, they will require a significant push from advocates to bring about. In recent years, several regions have revolutionized their transit service at little cost by redrawing routes. Bus transit service is flexible and there are many potential benefits to remapping and rerouting existing service.

In most regions, bus service continues legacy routes from suburban areas into downtown. But today, many job centers—especially for low-wage workers—are no longer concentrated downtown. Bus service should better serve commutes to suburban job centers.

Meandering, overlapping bus routes are slow and inefficient.

Example

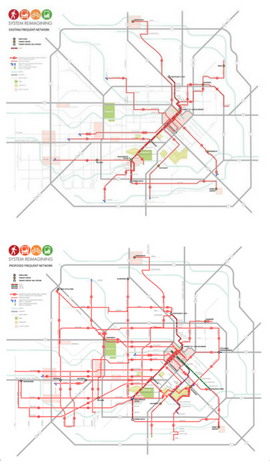

Houston: Under the leadership of Christof Spieler, a regular bus rider who was named to the board of Houston Metro, the agency comprehensively redesigned its bus routes. Service had not been completely redesigned for generations and the result of decades of incremental changes was a slow, twisted, fragmented system. Trips cross-town or to destinations outside of downtown were especially difficult—even though major job centers had grown out of downtown.

Under the new plan the number of people living within a half-mile of frequent service jumped by 117 percent and the number of jobs within a half-mile of frequent service increased by 56 percent, all for nearly the same cost as the previous service arrangement.

After two years of new service, Houston’s bus service continues to attract more riders even as most major cities are seeing the number of transit riders fall.

Such a route redesign requires hard choices and can be disruptive for riders. There is an inherent tension between providing service to the most places and providing fast and frequent service. When Metro planned to eliminate certain stops and routes to speed service, the agency faced vocal criticism at public meetings. While the agency initially sought to design a new system to run at exactly the same cost, it ultimately elected to set aside an additional $10 million (three percent of the annual operating budget) to reinstate service that would have been eliminated.

Houston’s frequent bus system before and after the redesign. (Photos courtesy of Houston Metro.)

Often, it takes years of planning and considerable political capital to make big, permanent improvements to transit. New rail or bus rapid transit lines could have a transformative impact in your city or neighborhood, but they may also take too long or be too expensive to deliver the improvements you need now.

Some cities are pioneering smaller, faster approaches to improving transit with low-cost, sometimes temporary, changes to streets and bus stops. These types of improvements can go in the street much more quickly and so offer better service sooner.

Tactical projects include bus-only lanes or transit signal priority at particularly slow spots along bus routes or consolidating stops to speed buses and ease transfers.

Examples

Everett, MA: Everett, Massachusetts lies just four miles north of downtown Boston. Without a subway stop, the city depends on buses for transit. Nearly 19,000 residents ride a bus each work day, and these riders were caught in grueling rush hour traffic. To speed these riders’ commutes, the city repurposed a lane from street parking to bus-only travel for the morning rush.

The dedicated lane was launched on a temporary basis, with just a row of orange construction cones to mark off the new bus lane. But it quickly proved its worth and the city chose to indefinitely extend the pilot project. Preliminary data showed that the new bus lane shaved four minutes off of bus riders’ commutes. Rather than waiting for big new investments from the state transportation department, the city wanted to “take transit into its own hands,” said Jay Monty, Everett’s transportation planner. “It’s pretty simple to put some cones down and just see what happens.”

After months of running a successful pilot, the city made the arrangement permanent by painting and using signs to mark the bus lane. Along with lane markings, the city is developing new transit-priority signaling which will allow buses to travel more quickly though intersections with traffic lights.

Given the success of this first tactical bus lane, MassDOT hopes it can be a model used on other congested streets across the state. Ninety-five percent of riders surveyed said the state should pursue additional bus lanes.

Washington, DC: Washington, DC has also applied a small-scale approach to bus improvements.

While transit advocates in the District and across the region have called for new bus lanes along major corridors, the District Department of Transportation (DDOT) took advantage of a repaving and streetscape improvement project to add a short bus lane.

The new four-block bus lane targets one of the slowest segments of Georgia Avenue, where buses carry 20,000 riders a day. The project, which required only a minimal investment of red paint on the pavement and new signage, quickly improved transit travel times through this section.

The Georgia Avenue bus lane project grew out of the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development and the Office of Planning’s plans for redeveloping and revitalizing the lower Georgia Avenue corridor. The District hoped to revive a once-vibrant area to be more of a destination with restaurants, bars, shops, and entertainment venues. As part of this larger effort, DDOT commissioned a study on transit and mobility on Georgia Avenue and the surrounding area. Federal funding from the TIGER program was allotted for bus improvements and had to be spent by a fixed deadline, so planners were looking for projects that could be completed quickly and have a big impact.

While many drivers complained of conditions in the area and bus riders complained about buses stuck in traffic, the plans DDOT proposed were not well received by members of the surrounding community. Representatives from Emergence Community Arts Collective and Howard University’s Community Master Plan noted many community members’ opposition to the project. Community members feared the disruption from street reconstruction, opposed the removal of street parking, and worried that transportation changes would speed gentrification, and yield higher rents and displacement.

While DDOT developed plans for the Georgia Avenue bus lanes, advocates led by the Coalition for Smarter Growth advocated for bus projects across the region and specifically along the parallel 16th Street corridor. A District-led study has recommended bus lanes along this route, but construction has not yet begun.

Dedicated bus lanes along Georgia Avenue. (Photo credit: BeyondDC.)

Chicago: Advocates from the Active Transportation Alliance—an organization supporting people walking, biking, and riding transit—found that bus ridership was sharply declining, in part because of poor quality service.

Even as CTA, the transit agency, planned new, high-quality bus rapid transit line on Ashland Avenue, advocates wanted to bring additional improvements more quickly to corridors across the city—especially in the disadvantaged South Side.

The Alliance’s Back on the Bus coalition focuses on incremental, low-cost improvements that can speed up transit and make bus service better for regular riders and attract more people to take the bus. Tactical improvements include speeding up bus boarding by allowing riders to pay before getting on the bus, speeding buses through traffic by dedicating lanes to buses, and giving buses priority at intersections and through traffic lights.

The Alliance surveyed riders about their experience riding the bus and what factors they would prioritize for improvement.

The city’s first major project to speed up buses was the “Loop Link,” dedicated, red-painted lanes for buses through downtown along with new lanes and sidewalks for people biking and walking. Active Trans collected comments from bus riders using the new lanes.

Ian Adams, a 29-year-old Ukrainian Village resident who works in the Loop, said, “getting to the Loop is pretty straightforward, but transit within the loop is really lacking. I’ll likely ride the bus more often with the new corridor and ride my bike in the new protected bike lanes when the weather is good. I’m in business school in Streeterville and need to get across the Loop in the evenings when the streets are totally jammed.”

Advocates pointed to successful bus improvement projects in peer regions across the county to show how these projects could be successful in Chicago. The alliance continues to advocate for expanding the meager network of protected bus lanes and better enforcing the lanes the city has designated. Read more here.

For transit to work well, people need to be able to easily get to stops and easily get from stops to where they are going. Streets need to be safe and inviting for people walking to and from stops. Complete Streets, which are designed for people driving, walking, biking, and riding transit, are a key to making transit work.

Removing barriers and improving access to transit depends on advocacy and partnerships between transit agencies and other governments, including (depending on the street) city, county, or state transportation departments.

Examples

Portland, OR: TriMet, the regional transit agency in Portland, has led a planning effort with city and county governments to identify street improvements to help people more safely reach transit stops. The Pedestrian Network Analysis Project analyzed 7,000 stops across the region to make specific recommendations for other governments to include in their transportation and community plans. Read more here and here.

Atlanta: Frustrated with the limited information posted at the 10,000 bus stops across the Atlanta region, the MARTA Army—a grassroots, self-funded, start-up advocacy group—“adopted” 350 bus stops. MARTA Army printed and laminated their own informational signs and fixed them to bus stops, providing schedule and route information to riders (or potential riders). The organization also fundraised to buy eighty new trash cans, which the city of Atlanta installed at bus stops. Read more here and about the MARTA Army here.

New, technology-powered transportation services—like Uber and Lyft—can be a valuable complement to fixed route transit service. These services can be especially valuable in providing first- and last-mile connections, to get riders from their homes to a transit stop, or from a stop to their final destination.

As valuable as these new services are in complement with fixed transit service, they cannot be a complete replacement for transit. There is no way for a fleet of cars to match the efficiency of bus service; even a nearly-empty bus carries many more passengers than a full Uber or Lyft sedan. Moreover, these services are very new and still experimental. While there is the potential for symbiotic connections between private transportation network companies and public transit, the private providers can pull up stakes at any point. Without public transportation options, such a service cut would be a crisis for riders who depend on transit.

Across the country, cities and transit agencies are experimenting with new partnerships with these providers. Advocates can push for new connections that improve service for riders, while not destructively eliminating the fixed routes that serve as a backbone for transit service.

Example

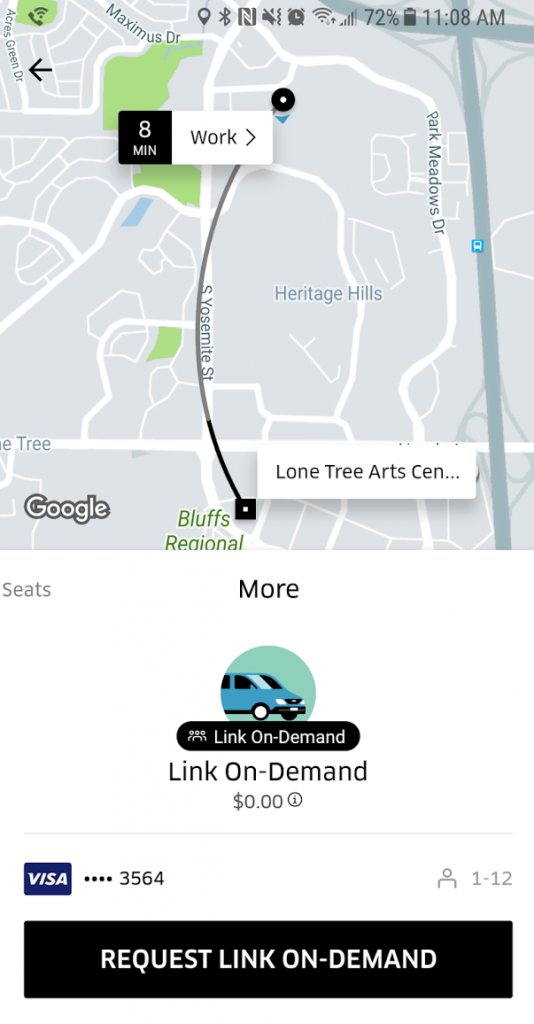

Lone Tree, CO: Lone Tree, Colorado, one of the 16 members of T4America’s Smart Cities Collaborative, successfully launched a new pilot project, augmenting their existing fixed-route circulator served by four small buses by adding an on-demand component through a partnership with Uber. The city’s Lone Tree Link On Demand service pairs Uber’s technology with the city’s vehicles and drivers to expand an existing shuttle service (that primarily served a light rail station) to more residents and increase accessibility. During the pilot, anyone can use the Uber app to hail a Lone Tree Link shuttle for a free ride between any two points within the City of Lone Tree. Read more here.

Lone Tree, CO: Lone Tree, Colorado, one of the 16 members of T4America’s Smart Cities Collaborative, successfully launched a new pilot project, augmenting their existing fixed-route circulator served by four small buses by adding an on-demand component through a partnership with Uber. The city’s Lone Tree Link On Demand service pairs Uber’s technology with the city’s vehicles and drivers to expand an existing shuttle service (that primarily served a light rail station) to more residents and increase accessibility. During the pilot, anyone can use the Uber app to hail a Lone Tree Link shuttle for a free ride between any two points within the City of Lone Tree. Read more here.

Lone Tree Link on Demand powered by Uber. (Photo courtesy of Lone Tree link.)

.

.

.

Both workers and employers have a keen interest in ensuring transit service provides access to jobs. Employers depend on access to workers from across the region. Access is particularly challenging at suburban job sites with lower-wage jobs.

Several innovative new partnerships show how employers and transit agencies can partner to extend transit service to serve employees.

Transit advocates, economic development groups, and workforce development organizations can work together to identify transit needs and form new partnerships to create and fund transit to serve employees.

Examples

Groveport, OH: Many growing, suburban job sites are inaccessible to workers because they are cut off from conventional transit service. Major centers of logistics and manufacturing jobs—sectors that offer some of the best opportunities for workers with limited education—are particularly isolated because they are necessarily located in lightly populate areas. Conventional, fixed route transit is not well suited to sprawling, isolated campuses, factories, or warehousing sites and the specific, non-peak times throughout the day that workers arrive and depart.

Poor transit access challenges both employers and potential workers. Businesses would like to recruit the workforce they need from the largest possible talent pool. There are potential workers who would take these well-paying jobs, but lack the reliable transportation to reach them.

The small city of Groveport, Ohio, (pop. 5,400) is located 15 miles south of Columbus and hosts nearly 20,000 logistics jobs at the region’s major intermodal port. Logistics companies struggled to fill temporary positions during the 2014 holiday season and one company began its own shuttle service to and from Columbus. When the shuttle proved a success, companies worked with the city to launch a full time shuttle service connecting with existing regional bus service in 2015.

“I’ve heard over and over again that recruiting employees and getting them to work is at the top of the list of needs for our businesses,” said Groveport Mayor Lance Westcamp.

The City of Groveport, along with the neighboring Village of Obetz, are financing the new shuttle service. Shuttles are timed to shift changes at the area’s businesses. Riders pay no extra fare to ride the shuttle. Read more here and here.

Workforce development groups cheered the new service. “Transportation to the Rickenbacker area has been a challenge for prospective employees,” said Lynn Aspey, director of business relations for Jewish Family Services in a press release from the regional transit agency. “Now this hurdle has been eliminated…As a result, candidates will have greater access to 21,000 jobs within the Rickenbacker area.” More info from Groveport is here.

Partnerships between private logistics companies and public transit have also launched in Indianapolis and Milwaukee to help workers reach remote job sites.

Atlanta: Coca-Cola wanted to provide transportation options for 7,000 employees who work at the company’s Atlanta headquarters. Atlanta’s highways are some of the most congested and offer the most unpredictable day-to-day commutes in the country; the one-way commute on GA Route 400 can be as much as three hours. New company shuttle buses connect the company’s two offices with the Five Points MARTA station, allowing employees easy connection to the regional mass transit network. To further encourage employees to use MARTA transit, Coke offers a $50-per-month transit benefit, enough to cover half the cost of a monthly pass. Now up to 500 employees arrive by transit, according to Eric Ganther, who heads Coca-Cola’s employee transportation efforts. Read more here.

Public transit is a vital tool to expand access to opportunity for individuals with low incomes. Yet transit fares are prohibitively expensive for some riders, especially youth. For a very low overall cost, transit agencies, local governments, or service organizations can subsidize transit fares and make sure the benefits of transit are available to all.

Transit advocates, community, youth, and social equity organizations can lead efforts to ensure that transit fares are not a barrier to accessing jobs, education, health care, or other needs and opportunities.

Example

Boston: Through a nearly-decade-long campaign, youth advocates in Boston compelled the MBTA transit agency to offer low-cost transit passes for youth. Read the Boston story at the conclusion of this document, one of three longer case studies included in this guide.

Vital improvements can be made to your region’s public transit service in the short- and medium-term through the operational and tactical improvements considered above. But there is also a vital role for transit advocates to play ensuring that your city and region support transit and well-connected neighborhoods over the long term. Building from a tactical campaign into an ongoing movement for transportation reform allows your coalition to influence long-term planning decisions.

Example

Bay Area: The 6 Wins Campaign in the Bay Area of California unites housing, equity, environmental justice, and transit advocates who have pushed regional planning agencies to adopt a more equitable long-range plan and short-range program of projects. The coalition developed the Equity, Environment and Jobs Scenario for transportation and housing, as an alternative to the long-term planning scenarios considered by the Metropolitan Transportation Commission and Association of Bay Area Governments. The scenario includes an additional $8 billion investment in transit service, as well as more housing options with access to jobs centers. The coalition advocates for the inclusion of these equity policies and funding priorities in the region’s 2017 Plan Bay Area update. Read more here.

Boston

MBTA Secretary Stephanie Pollack cutting the ribbon on the new Youth Pass in 2015. (Photo credit: MassDOT.)

Even in neighborhoods with good transit service, young people in the Boston region were cut off from opportunities because of prohibitively high transit fares. Community-based advocacy resulted in a new discount fare program to make sure that transit services is accessible for students and youth.

The new Youth Pass, launched by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA or the “T”) in February 2017, is the result of a nearly-decade-long campaign by young people in the Boston area who pushed MBTA for more affordable and dependable access to transit services. Youth leaders identified gaps in service, showed why the new pass was needed, and won small victories along the way. Youth organizers led efforts to collect stories and data, and then to engage MBTA on their findings.

Identifying challenges and launching the campaign

Facing challenges at school and beyond, young people of Alternatives for Community and Environment (ACE) in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston hosted a series of conversations in 2007 to talk about root causes of their neighborhood’s disadvantages and identify possible solutions. Through the conversations, the young advocates found the high cost of public transportation to be a critical obstacle for many. Youth relied on public transit get to and from school, extracurricular activities, jobs, and medical appointments and the expense of transit fares was a financial strain. The burden was especially heavy for students from low-income families and students of color. The young people at ACE learned that many peers and their families were having trouble paying full-cost fares to get to school, work, and other activities. In response, ACE launched their “Youth Way on the MBTA” campaign to further explore the problem and push for solutions.

At the time, MBTA offered discounted fares for students, but these passes had limited hours and excluded youth not in school. The student passes, or Charlie Cards, were purchased in bulk by the Boston Public School System and distributed to individual students through participating schools. The Student Charlie Card was only available for use on weekdays until 8:00 p.m., which created another barrier for youth whose school, work, or other activities required that they travel later on weekdays or at any time on the weekends. In addition, some schools did not even participate in the program. Some of the students who couldn’t access transit discounts had to walk or find other means to get to school, jobs, and extracurricular activities, making it hard for them to arrive on time. Others simply missed days of school or other commitments altogether because they could not afford transportation.

ACE’s youth leaders began meeting with MBTA staff to explain their challenges, request changes in the student program, and ask that something be done to make transit more affordable. To bolster their lobbying, ACE collected and delivered 1,600 postcards to MBTA documenting service gaps and the problems with the Charlie Card program as further proof the program needed to be improved.

These petitions secured the first win for Youth Way on the MBTA campaign; MBTA agreed to extend the evening hours for the student pass from 8:00 p.m. to 11:00 p.m. While this was an important first step, it did not solve the issue of affordability. The discounted student fare passes were still only available through participating schools and there were other young people, not in middle or high school, who needed access to more affordable fares.

Making the case with surveys and research

Youth leaders continued to press for transit affordability with youth-focused surveys, reports, public demonstrations, and meetings with transit officials.

In 2011, ACE and partners published the report, “OpportuniT: Youth riders, the affordability crisis, and the Youth Pass Solution.” The report was based on 2,400 surveys ACE collected in 2010 along with the information the young people had gathered through over 4,000 listening sessions and conversations they had held since the beginning of their campaign. The report told the stories of students and young people not able to afford fares and the impact it had on their ability to attend school each day, get to doctors’ appointments, get home safely after work, and more. It showed the gaps in service left by the Charlie Card program, and proposed the creation of a new Youth Pass to supplement the student fare.

Youth leaders had regular conversations and interactions with MBTA. In 2011 MBTA general manager Richard Davey told advocates that the agency would conduct a pilot of the youth pass program. To celebrate his support, ACE and other youth transit advocates honored Davey and other MBTA staff at their annual banquet for their support for youth transit access.

However, as MBTA faced (and is still facing) a growing budget crisis, the promised youth pass did not come to fruition. It took several more years of youth advocacy to get the youth pass program off the ground.

Growing the movement and turning up the pressure

In 2012 MBTA proposed across-the-board fare increases, including increases to discounted student and senior passes. In response, youth advocates formed the Youth Affordabili(T)y Coalition (YAC). It included ACE, their youth transit partners, and youth groups ranging from young immigrant support groups to students from area schools. YAC’s organization significantly increased the number of young people participating in the coalition and actively advocating for the youth pass.

In March 2014 youth leaders testified at a MBTA hearing and delivered a petition with more than 1,500 signatures. Following the hearing, the youth leaders planned a protest to further draw attention to the cause.

“We’ve been bringing this issue to the MBTA for more than seven years,” said march organizer Javon Morris, 17. “The T is continuing to raise fares and ignoring the fact that many youth depend on public transit and already can’t afford it. We have done our part. It’s time for the T to do theirs.”

This effort helped YAC secure a win. MBTA announced that for the 2014-2015 school year, student Charlie Card service would be extended to seven days a week and there would not be a fare increase. The price for the 7-day pass was the same as the previous 5-day pass. The advocates were pleased with the news, but were upset that MBTA postponed the youth pass pilot project that MBTA promised in 2011. YAC addressed an open letter to Richard Davey (who had then been promoted to MassDOT secretary) asking him to make good on the promise made years before. They stressed that the implementation of the pilot program could be revenue neutral, meaning it would not cost the agency any additional funds. Days after sending the letter, YAC staged a march with hundreds of youth calling for the creation of the youth pass and the pilot program. They earned significant media attention, but were told that the pilot program would not be possible due to budget constraints.

YAC did not abandon the cause and continued by staging acts of civil disobedience. On June 10, 2014, 30 YAC members participated in a sit-in at the Transportation Building to protest the pilot program’s delay.

“It’s not something we want, it’s something we need,” said marcher Trae Weeks of Roxbury, interviewed by NECN news. “I see kids stranded every day at train stations. I see bus drivers kicking kids off buses because they don’t have funds.”

Twenty-one people were arrested. Their protests, sit-in and the arrests garnered more local media attention for their cause.

Temporary victory: pilot program

Finally, on June 25, MBTA’s general manager Beverly Scott agreed to conduct a year-long youth pass pilot project in 2015. Soon thereafter, the MBTA formed a working group with YAC leaders to design the details and logistics of the program. YAC worked to make the pilot program a success by agreeing to help get the word out about the new program.

Four municipalities agreed to participate. The cities of Boston, Chelsea, Malden, and Somerville agreed to take on the task of administering the program, accepting applications, and distributing the fare cards. The cities had existing programs providing youth services, so they were eager to have even more young people coming to their offices and centers. They believed that having youth come to their offices to apply for the discounted fare pass would provide an opportunity for them to get plugged into other services for city youth. The pilot program was a success.

The structure of the pilot allowed MBTA to objectively measure the program’s effectiveness, which is rare for new social programs but was necessary while the MBTA was under the strict watch of the Fiscal Management and Control Board (FMCB). A preliminary report published in December of 2015 showed that even though participation was low at that time, youth ridership increased with the passes and the program showed significant benefits and increased transit ridership among low-income and minority youth. Without the discounted fare, most of the participants said they would not have made trips on the T and, in many cases, would not have attended school or GED class, scheduled doctor’s appointments, or work. The results showed that passes were utilized by many young people not eligible for the existing MBTA student pass because their schools did not participate in the program, or for other reasons.

Winning

On June 6, 2016, the FMCB voted unanimously to extend Youth Pass program as a permanent program. Based on the pilot results, board members were convinced of the program’s benefits. In fact, the pilot data was so strong that the Board approved a presenter’s suggestion that the program be made eligible for youth up to age 25.

Eligible students and young people aged 19-25 are able to purchase a monthly pass for $30.00, which is 62 percent less than the regular monthly MBTA fare pass ($84.50). The Youth Pass is now offered for young people ages 19-25 in 17 municipalities in the Boston area.

Lessons learned and keys to success

Looking to replicate this grassroots campaign success in your city? YAC’s success came from persistence and creative tactics to continue to push this issue. Here’s what it took:

- Youth-led surveys, petitions, and reports showed why young people needed an improved MBTA Student Pass discounted fare program.

- Strong allies and partners, regular communication and engagement with public officials, publicity, and public education campaigns placed a spotlight on the issue.

- Youth advocates built champions inside the transportation agency by meeting with transit officials often, agreed to work with them to find solutions, offered solutions based on data, and honored and recognized officials for their support.

Through traditional and creative communications and public relations campaigns, youth and their transit advocacy partners were able to raise awareness about the negative impacts of high fares on young riders’ access to school and jobs. Protests and demonstrations drew public attention to the issue of transit affordability for youth and other riders.

The campaign depended on persistence and attention-getting tactics that demonstrated that youth activists were not going away. Youth launched the effort in 2007 and continued to demand youth rider affordability, even as they were told it would be impossible.

Indianapolis

IndyCAN volunteer talking to a transit rider/supporter during their Ticket to Opportunity campaign. (Photo credit: Faith in Indiana, formerly IndyCAN)

In 2016, transit advocates in Indianapolis scored an important victory when voters approved a local income tax hike to fund expanded transit service. The chamber of commerce and faith-based community led a diverse movement to win the support needed. Transit backers cleared the last hurdle with a city council vote in February 2017—the final step in a long path to win local funding.

Winning legislative permission

Indiana municipalities lacked the authority from the state to raise taxes for transit, so it took a lobbying push, targeting Republican and Democratic legislators from across the state, to win the enabling authority for a local option tax. The transit coalition won a legislative victory in 2014, but it came with caveats: the city-county could approve a local, supplemental income tax (no sales tax), but only with the approval of the City-County Council, approval through a county-wide voter referendum, and then another approval from the Council. Read more here.

Community leaders developed the region’s transit plan, adopted service changes to boost ridership and offer faster service on existing lines, and won federal funding to begin work on the region’s first bus rapid transit line, connecting the region from the more affluent north to the more impoverished and disadvantaged south. Through 2015 a new batch of community leaders joined the transit effort through participation in the Transportation Innovation Academy, which T4America cohosted with TransitCenter.

As the region prepared for a ballot measure to expand funding for transit, the transit agency also shifted existing resources to provide faster service for more riders. Before the change in service arrangement, the top three busiest bus routes accounted for 40 percent of bus boardings. The new service pattern moved buses to faster and more frequent routes. After the change, 80 percent of the system’s service was on routes intended to attract the most riders.

Campaign

Once the City-County Council voted in May 2016 to put the measure on the November ballot, campaign efforts sprang into action. The referendum campaign had three components:

- An education campaign led by public agencies, including IndyGo, the transit agency;

- A political campaign, named Transit Drives Indy, led by the Indy Chamber and MIBOR, the regional realtors’ association;

- And a grassroots mobilization effort, anchored by the Indianapolis Congregational Action Network (IndyCAN).

Transit Drives Indy raised a reported $500,000 to fund polling and voter modeling, direct mail, social media advertising, and other voter engagement efforts. The campaign reached half a million voters with nearly 1.7 million on-air impressions from campaign ads.

IndyCAN’s “Ticket to Opportunity” campaign trained 1,248 volunteers to be supportive voices for families whose lives would be improved by better public transportation. Those volunteers made 165,000 calls to educate other Indianapolis residents about the benefits of public transit.

This direct communication was critical. “It was just educating people about what this transit plan would do,” said IndyCAN organizer Nicole Barnes. “You can have all the signs and fliers you want, but there is nothing like having a real person who can answer your questions right on the spot.”

The campaign succeeded by connecting these investments in transit with the city’s pressing concerns as well as its aspirations.

“This was more than just a vote about buses and trains,” says Shoshanna Spector, executive director of IndyCAN. “It was a way to answer the question ‘Do we as Hoosiers and residents of Indianapolis believe in investing in people and investing in our neighbors?’ The overwhelming answer is that we do.”

The different components of this transit effort were all necessary to win decisive approval at the ballot box. The Chamber and MIBOR brought substantial resources to the table to raise the profile of the transit referendum in a crowded campaign season. The grassroots organizers could speak authentically to transit riders and low-income communities and counter concerns about the proposed plan from some neighborhoods and communities.

Results

The plan approved by voters will boost IndyGo funding by $56 million annually by adding a 0.25 percent supplemental income tax. The new funding will allow for more frequent buses on faster routes and the construction of three new bus rapid transit lines. Before the new funding and service improvements, just two lines had buses arrive more than twice an hour. With new funding, IndyGo will provide service every fifteen minutes on most lines, all day, seven days a week. The Transit Drives Indy campaign highlighted that with new service, by 2021:

- 247,985 jobs will be within a ½ mile of a frequent transit route (arriving every 15 minutes), compared with 140,057 jobs today.

- 45 percent of Indianapolis’ minority population will have access to a frequent route, compared to 14 percent today.

- 32,770 low-income households will have access to a frequent route, compared with 10,517 households today.

Lessons learned

Be persistent. It took advocates three years of lobbying to win local funding authority another two years to develop a successful ballot campaign and two votes in the City-County Council to secure the transit funding.

Build consensus so that transit supporters are all pushing in the same direction. While the grassroots organizers and the business-led campaign were not working together directly—and could reach different audiences by focusing separately—the coordinated effort was critical to success at the ballot box and throughout the campaign. Both the business and grassroots were vital.

Baton Rouge

Saving a transit system and turning the tide for the future of a mid-sized city. (Photo courtesy of Together Baton Rouge.)

In 2012 the citizens of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, voted to raise their taxes to preserve and expand their struggling bus system. The landmark measure nearly doubled transit funding—saving the system from meltdown while laying the groundwork for dramatically improved service. To pass it, churches, faith-based groups, and local organizers teamed up with businesses and institutions.

Even before the prolonged fiscal crisis, Baton Rouge’s Capital Area Transit System (CATS) struggled from underfunding. Service had degraded to the point that the wait for a bus exceeded 75 minutes and average rides were over two hours long. The system was saved repeatedly only by last-ditch city budget shuffles, creative grants, and even private donations. The biggest blow came when Louisiana State University, after years of student complaints, backed out of the CATS system and contracted with a new (more expensive) private operator. That meant a loss of $2.4 million from CATS’s annual budget.

In 2010, a parish-wide tax to support the transit system failed at the ballot box, in part because large parts of the parish (same as counties in other states) do not use or have access to the service. When projections came in that the transit agency would be so far in the red they would have to shut down in summer 2011, it became painfully clear that something major needed to be done.

After cobbling together grants and funding to make it through 2011, the mayor appointed a Blue Ribbon Commission to make recommendations not only to save the service, but to create something much better. But the first job was to save the system, as Rev. Raymond Jetson, the chair of that commission, told the Baton Rouge Advocate: “Before there can be a robust transit system, before you can do novel things like light rail between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, and before you can have street cars from downtown to LSU, you have to have a backbone to the system,” he said. “And that backbone is a quality bus system.”

Funding that system depended on a ballot measure to approve a 10 year, $10.6 million property tax.

Before putting a funding measure to voters, the commission recommended significant reforms to the composition of the transit board and an end to the ability of the Metro Council to veto the board’s decisions. “Governance reform and long term accountability … helped separate it from the previous failed measures,” said Broderick Bagert of Together Baton Rouge, a broad, multi-racial, faith-based coalition of institutions backing the measure.

How did they do it?

The first step was to build the core coalition that would push this measure to victory.

Together Baton Rouge was a relatively new organization that led the way as the grassroots behind the measure. They coordinated call banks, get-out-the-vote rallies, more than 120 educational “transit academies,” and door-to-door canvassing of tens of thousands of homes by hundreds of volunteers. They began with three informational meetings with 300-400 people each, where “community members told other community members why things were bad and what the new plan was,” said Bagert.

“We asked two questions on the sign-in card: ‘Do you want to be part of a voter outreach campaign?’ and, ‘Are you part of an organization and would you be willing to organize one of these sessions?’ We built a strong base of people that wanted to help do outreach and educate their fellow community members.”

In part because of the groundwork of the Blue Ribbon Commission and other partnerships, the Baton Rouge Area Chamber got on board along with other business groups. Hotels and hospitals, whose leaders realized how much of their workforce depended on CATS each day, joined in.

Colletta Barrett, vice president at Our Lady of the Lake hospital system, told The Advocate that 10 percent of OLOL’s staff, or 400 people, use CATS:

“It is imperative,” she said, “that a transit system is available to move people from north Baton Rouge to the medical corridor in the southern part of the parish. It’s unacceptable that it takes an hour and 45 minutes to get to this side of town. We have told our employees that we have an individual social responsibility to take care of each other.”

Ralph Ney, General Manager for the local Embassy Suites hotel said about 15 percent of his workforce uses CATS to get to work, which sometimes results in his employees being late.

“It’s difficult to hire and maintain employees who don’t have transportation,” said Ney, who was a member of the Blue Ribbon Commission. “It’s evolved to where a lot of our employees don’t even take the bus because they can’t get to work on time, so they’re riding bikes or catching rides.”

A key part of the coalition was the Center for Planning Excellence (CPEX), a non-profit that helps Louisiana communities with planning issues. They became involved through their CONNECT initiative to build a diverse coalition across the New Orleans to Baton Rouge super-region to advocate for smarter housing and transportation investments. The CONNECT initiative concluded that one of the critical pieces for regional connectivity is a viable, robust transit system serving the metro area. This was also strongly recommended in the new comprehensive plan for Baton Rouge, called FutureBR.

CPEX worked with many of the former members of the Blue Ribbon Commission to create the Baton Rouge Transit Coalition, a diverse set of partners who provided information, resources, and conducted educational outreach to the Baton Rouge community. They hosted numerous outreach meetings, advocated for the changes to CATS governance in the state house, created a website that became a clearinghouse for facts and research during the campaign, and worked closely with the Baton Rouge Area Chamber to solicit support from the business community—in addition to being a strong part of the grassroots effort led primarily by Together Baton Rouge.

In the end, the boosters of the transit measure had built a coalition that had strong grassroots, wide reach, and a diverse range of interests. Without the participation of any one of the core coalition members—Together Baton Rouge’s grassroots and trusted community members, CPEX and their coalition of transit boosters, and the area Chamber and the business community—the effort would not have had the same success.

Trusted messengers—and message

Bagert summed up this strategy simply: “We let the community leaders be out front leading the way. Not professionals, not paid staff, not elected officials, not transit officials.”

“One of the strengths of this effort was that the plan was created by community leaders and many of the important people were already behind the plan,” said Rachel DiResto of CPEX. “It certainly took some effort to get new folks on board, but the important pillars were already on board. We didn’t need to convince them.”

For the message, especially in the key districts with heavy transit usage and service, the campaign kept it very basic, “Save our system.” They noted that Baton Rouge was the only city of its size without a decent transit system, and talked about the people who depend on it each day: perhaps the nurse who cares for your mother at the hospital, or your neighbor or friend. The campaign steered clear of some of the typical statistics in transit campaigns about reducing traffic congestion, gas prices, or environmental impacts.

Stories about the hospital and hotel workers showed how the advocates built a larger, inclusive narrative and a vision for the community’s future. Events were filled with personal stories and made the impact of the system (and the potential impacts of not having it or having it improved) clear to everyone, regardless of who they were, where they lived, or whether or not they rode CATS.

“Outreach, outreach, outreach”

To deliver that message, Together Baton Rouge and the coalition held an ambitious number of community outreach sessions they called “transit academies” or “civic academies” in churches, community centers, and other venues. In the four-month campaign leading up to the April 21 vote, they hosted 120 of these sessions.

“Anywhere anyone wanted to hear more, we did a presentation,” said DiResto of CPEX. “And it paid off with more people who hadn’t been active voters showing up at the polls for a special election.”

These meetings were largely targeted to areas and precincts where support and heavy turnout would be needed to shift the outcome of the vote. “The diversity of those meetings was a huge plus,” DiResto said. “People who would never ride CATS were sitting in the same meetings with those who ride it every day. And their stories really impacted the former.”

The Advocate told one story about Fred Skelton, a 70-year-old Baton Rouge homeowner who had never ridden a CATS bus before, but understood how important the service was for riders. During one community meeting he said he would be “first in line at his voting precinct to support” the tax. The reason, he said, is because before his mother died, she used to stay at a nursing home where he’d visit her. When he visited, he said, he remembered frequently seeing groups of employees waiting for the bus.

“Those people who were waiting for the bus are the people who were taking care of my mother,” he said. “If we shut down the transit system, who will take care of those people?”

Strategic precinct targeting

Resources are always limited in a campaign, and therefore best deployed where they can make the most impact. The overall strategy—change minds of people on the fence, increase support from typically opposed groups, or focus primarily on the base—determines where resources should be targeted.

One of the biggest differences between this successful measure and the recent failed measure in 2010 was the use of more strategic targeting of resources in key precincts. Though the campaign did deploy some resources in suburban areas with small amounts of service, mostly to blunt opposition, the brunt of their efforts focused on getting out the vote in their strongest precincts.

“We did detailed analysis of the electorate,” said Bagert. “We referred to the recent failed measure for background, which helped analyze the lay of the land. We focused our direct energy on turning out the strongest [most supportive] precincts, leaving out voters that had no voting history in the last 4 years. We tried to get 10 percent of the 2008 presidential election voters to vote for the measure.”

As a result of this strategy, the campaign was well poised to bounce back and succeed when The Advocate threw a curveball late in the game and editorialized against the transit tax, which likely cost the campaign a significant amount of support in precincts with already low support or significant numbers of undecided voters.

Making the benefits tangible and measurable

Voters need to know what their dollars are really “buying” at the end of the day. How will they better connect workers with jobs, make their lives easier, or save them money?

Given the perception that CATS was a poorly governed money drain, simply offering up a plan to pour money into CATS and hope for the best was not going to fly. People had to be inspired to believe that things actually would get better.

To demonstrate clear improvements and hold the agency accountable, the coalition offered a list of promised CATS improvements:

- Decreased average wait times for buses from 75 minutes to 15 minutes.

- Eight new express and limited stop lines, serving the airport, universities, mall, and other key destinations.

- GPS tracking on the entire fleet, with exact arrival times accessible on cellphones.

- New shelters, benches, and signage at bus stops.

- Expanded service to high-demand areas and nearly doubling the number of routes.

- Three new transfer centers operating in a grid system to replace the outdated hub-and-spoke route system.

- A foundation for bus rapid transit.

Winning

The transit ballot measure was approved on April 21 in Baton Rouge, 54 percent to 46 percent and the municipality of Baker, 58 percent to 42 percent. In Zachary, a more suburban area with little service, it was rejected, 79 percent to 21 percent. Early returns showed the measure losing overall with only 40 percent support, but “then the precincts we had worked came in and voted in historic levels, supporting the measure at around 90 percent in those key precincts,” according to Bagert. “The key was really getting strong vote in supportive precincts.”

Advice for others

Facing a ballot measure in your area? Planning one? Here are four last smart pieces of advice to take with you from Rachel DiResto from CPEX.

- Bring core partners to the table early and find your champions who have to be willing to speak well to various audiences and who are willing to expend time and energy for your cause.

- Frequent communication with other partners is critical to maximize resources and not duplicate efforts.

- Focus on the outcome and target those folks who are supportive and mobilize them to show up to vote instead of spending all of your energy combatting those opposed.

- Know your message for various audiences.

Building accountability and success

The ballot measure win was a key victory, but CATS still needed significant reform to restore public confidence and put the agency on track to make the most of the new investments.

Following the referendum, Baton Rouge established a new citizen committee to review the qualifications and professional credentials of candidates to join the CATS board. This Qualifications Review Committee includes representatives from important civic organizations in the city, including Together Baton Rouge and CPEX, AARP, the Baton Rouge Area Chamber, Baton Rouge Hospital System, Louisiana Engineering Society, and Louisiana State University. The committee has helped recommend well-qualified candidates to the CATS board and also advertise board positions through broader professional networks.

CATS has excelled under new leadership. After a national search, the board chose to promote Bill DeVille, a transit veteran with 30 years of experience, to CEO in 2016.

According to DiResto, DeVille has built strong connections with transportation partners, including the city public works department and a new smart city committee. The agency won federal funding for new electric buses to replace an aging fleet and has met its commitment to improve bus stops and shelters. The agency is also evaluating and optimizing service and has cut or reduced underperforming routes while adding new service where it is most needed.

All these improvements will continue to build the agency’s standing in the community before it must ask voters to renew funding.

Appendix: How to Fund Transit Improvements

Where you look for new funding depends in part on the type of project your region needs

Capital projects are those that build or maintain infrastructure, or repair or buy new buses and trains.

Federal formula grant programs provide a fixed amount of funding annually to your local transit agency for repair and replacement. Separate formula grants are distributed through state departments of transportation and metropolitan regional transportation planning agencies. Federal grants through the Surface Transportation Block Grant program (STBG) can easily be directed to fund transit projects, as can funds from the Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ) program under most circumstances.

Federal competitive grant programs may provide additional funding to cover specific needs. Major new rail and bus rapid transit projects, or capacity expansions on existing lines, are eligible for federal Capital Investment Grants (CIG), commonly referred to as New Starts, Small Starts, or Core Capacity grants. These grants cover up to 50 percent of the cost of capital construction. Bus and Bus Facilities and Low- and No-Emission Vehicle competitive grants cover the purchase or repair of buses and facilities. TIGER grants are relatively small but can fund all types of infrastructure, including transit projects and street improvements.

While most federal transportation funding is dedicated through the Federal Highway Trust Fund and Mass Transit Account, funding for TIGER and for Capital Investment Grants must be annually appropriated by Congress from general revenues. That puts these programs at risk each year in the federal budget process—as they are being threatened now.

State funding can be an important source for transit projects. More than two dozen states have limits against using revenue from fuel taxes on transit projects, but other sources of state revenue (e.g. from sales, income, or business taxes) can fund all types of transit projects.

Transit projects often depend heavily on local funding. In many states, ballot measures can be used to approve new, local taxes dedicated to transit. Local governments and regional agencies can also reallocate existing funds, such as those within public works budgets, to fund transit priorities.

In rare cases, private or philanthropic funds may have also been used to support capital projects.

Operations funds pay for running transit service day-to-day.

Federal funding generally cannot be used for operations, except by the smallest transit agencies. The same state and local funding sources generally can be used for operations.

Innovative financing

In a time of constrained budgets, many regions have combined different sources of funding (e.g. grants) and financing (i.e. loans which must be repaid) to launch new projects. More detail on innovative financing tools and strategies can be found here.

Funding flows

Most federal transportation funds are granted to state departments of transportation. State DOTs control these funds and determine how they are spent.

There is wide variation in how much state transportation departments invest in transit service. Five states provide no transit funding at all, and another twenty provide less than $10 million per year. Five states annually direct over a billion dollars each to transit.

In urbanized areas of more than 200,000 people, Metropolitan Planning Organizations direct how federal funds are spent.